Total liberation

– Breaking bread until we are free –

Credits

Director, Editor and Narrator – Aron Nor

Writer and Narrator – M. Martelli

Art Director and Illustrator – Mina Mimosa

Music from Andrea Penso / Invisibilia editions

End Credits Song – Revolution by Eva Meijer

Video transcript

Imagine a table. Four legs, one flowery cloth draped over it. Plates and cutlery, shining. A big, steaming bowl of soup in the middle, surrounded by platters of juicy food. Father’s sitting. Uncle is pouring the drinks. Some people laugh, others pass the spices. They talk, small talk. Maybe someone says something a bit off, a bit `problematic`… others ignore it, keeping up the good spirits. No one wants to spoil the meal, right? There’s desert, too. Mother brings it. The young lick their fingers, it is that good! Can you hear the glasses clink?

Does this joy, this abundance, sound offbeat to you as well?

You don’t need to be told: you already know. Each series of actions, each material configuration holds within it so much of everything. Just pull one thread and unspool it:

The table. Who set it? Who cooked the food? Who did this work, and how was it recognized, if at all? Go further. The food, who packaged it? Who delivered it from where it grew? On what roads, over what borders? Who picked it or, if “it” had a heart, who killed… so that you could eat? If “it” was a part of someone, who was that someone? And who won the most out of this process?

Our tightly bound lives in a globalized capitalist world speak with a thousand voices – at each table, in every commute, every building and institution, there’s power to be untangled, privilege to be attentive to, histories to unbury.

We start this exploration of total liberation with the mundane scene of a family dinner. A table and the people around it. We start like this to nod towards those spaces in our lives that nurture us, that sustain our bodies & spirits. To look at how, even in those moments, there’s tension, buzzing in the air, connecting us to everything & everyone else.

A core ecofeminist principle would be to recognize we’re in relation, both to those close to us, and to far away beings and things. A core anarchist principle would be to challenge the hierarchies in which we’re entangled – to see and stand against them. A core anticapitalist principle would be to see history, and the present, from the point of view of those workers who make it all possible. But to anchor ourselves in a path towards total liberation would require more, it would require “an ethic of justice and anti-oppression inclusive of humans, nonhuman animals, and ecosystems”, as sociologist David Pellow writes in his analysis of this concept.[1] One thread of principles is not enough, we need to be able to weave between movements – to manifest what Angela Davis, an anti-racist activist and a socialist, calls the “intersectionality of struggles”.[2]

The table is easy to look at. You’ve been at a table. You know how it’s set. You grew up around it, in your mother’s kitchen maybe. It’s most probably your mother’s, or grandmothers’, or another woman’s, as women do most reproductive work worldwide – that work that’s rarely called work, that work that allows the worker to get back to his real “job”, that work that, if stopped, would crumble the world in its wake.[3]

The table is set because someone made it. Let’s assume something: that you live in a nation state caught up in neoliberal capitalism’s tangles. That the table you sit at is made of wood, carried over from decimated forests, sometimes legally, sometimes illegally. If it’s an IKEA table, there’s a high chance the wood comes from our region – Romania.[4] Think, beautiful oak tabletop, sourced from an old growth forest, home to brown bears, lynxes and wolves.[5] Their home is in your home now. But it’s not your fault, is it? The state could better protect its “natural areas” if only it wasn’t so tightly snuggled up with market forces. Indeed, many anarchists argue that the state’s function is, precisely, to protect private property and to work hand in hand with capitalists.[6] Assuming a monopoly over violence, the state decides who’s in and who’s out. The state legalizes what is right and what is wrong. The state becomes the only legitimate actor to protect those made weak or penalize those it finds at fault. It is the state that, by deciding the flow of resources and investments, distributes social inequality and permits the destruction of ecosystems. Activists such as Flower Bomb consider the state to be an “antithesis of liberation – reinforcing laws that utilize physical force to coerce all beings into compliance”[7].

States routinely exclude beings from having rights, often constituting themselves according to national narratives that are racist and almost always invisibilizing towards non-human animals. There are many examples of states trying to order the “natural world” according to their anthropocentric productivist vision and establish power through the domination of land. Some examples could be: the enclosure of the commons in 18th century England, the introduction of non-native species in European colonialism of the Americas, or the wide-spread practice of monocultures in agriculture and forestry.[8] Maybe you get a glimpse of how, for total liberationists, the answer to our struggles cannot be found neither from states nor capital. The table that’s set in a rented apartment, on a cemented road, in a polluted city, under a government that permits migrants only to underpay them, in a harsh economy that structurally disadvantages some to privilege others, creating competition and scarcity under the guise of meritocracy and efficiency… That’s not the table we dream of. It’s not the dinner we want.

What’s for dinner, then? In so-called developed countries (which often mean colonizer countries), in middle and upper-class homes, the table is full of products bought from a supermarket, brought from far away. It’s a complex system, and if you were some sort of alien, you’d get lost in it. Imagine these huge buildings, without sunlight, full of endless aisles of colorful plastic bags, each containing a variation of what you’re looking for. In wealthy areas, there’s endless variations: the aisles seem to never end. Biscuits, and biscuits, and biscuits, for as far as your eyes can see. Stacks of vegetables and fruits from all over the globe. And as you’d walk through the cold, bracing yourself towards where the fridges are, you find them: rows and rows of milk bottles and cartons, cheeses of many shapes, eggs and breasts, legs and wings, so many body parts you could never taste them all. So many body cuts. Yet in a world with so many choices, some are already made for us. Even the vegan options are sometimes merely add-ins, meant to make a profit for an all-encompassing market, for as consumption of vegan products grew world-wide, so did meat and dairy consumption.[9] Having “meat” at the table is, in many places, seen as a marker of development.[10] Yet what kind of development is this – towards what kind of world? Deforested for the soy monocrop plantations that become feedlot for cows, polluted from the slaughterhouses’ waste, and with an increasingly unstable climate from the rise in CO2.

Having privilege feels comfortable, until it doesn’t. But it’s not your fault though, is it? You were just born here, you took what you were given. Maybe you never had access to much, and what you have, you must take. So then… take it! Take more of it, and dream of more. More, not as in endless aisles, not as in colorful plastic bags. More, as in something else, a more in which you can fit in all your fullness, and in which those unlike you – other humans, other animals, other beings and ecosystems, can fit, too. Without being destroyed and without minimizing who they are. Can we dream of the kind of more that doesn’t annihilate the lives of others?[11] An anonymous anarchist once said that “animal and earth liberation can’t be dealt with afterwards, precisely because their liberation is the revolution. To prioritise human liberation over nonhuman liberation ensures we’ll get neither”.[12]

Maybe you disagree. But can you still sit at the table in peace, if what’s on the table has been bred, born and raised, only to be killed? Can we still call it liberation if some beings’ lives are entirely controlled, defined by being useful to some other beings? Can the food that feeds you really nourish you, you, not only your body but the fullness of you, if it’s ravaging forests and fields in the process, emptying & acidifying the oceans, disabling and traumatizing the workers?[13]

We talk of total liberation because we want it all. We don’t want some to be oppressed for someone else’s liberation. Historically, though, the concept emerged in the 90s, out of the colonialist, white-supremacist country known as The United States of America. Activists were trying to articulate ways of uniting animal and earth liberation with human liberation movements. They were organizing in informal, decentralized cells with consensus-based or democratic decision-making and attempting to “combat all forms of inequality and oppression”. The four pillars of total liberation, according to Pellow, are “anarchism, anticapitalism, an embrace of direct action tactics” and the already mentioned ethic of anti-oppression inclusive of all.[14] To these, Steven Best’s foundational definition would stress the importance of an “alliance politics with other rights, justice, and liberation movements that share the common goal of dismantling all systems of hierarchical domination and remaking societies according to new democratization and ecological imperatives”.[15] Activist Laura Schleifer adds that total liberation does not center the needs of any particular oppressed group, is influenced by multiple schools of political thought and is always trying to work in solidarity for collective liberation, rather than having privileged allies who try to help disenfranchised others to rise up to the status quo.[16] The term itself was first used by anticolonial Marxist thinker Franz Fanon, as writers Sarat Colling, Sean Pearson & Alessandro Arrigoni make known. Following Fanon, they add that “Total liberation can only be achieved through a commitment to the destruction of the colonial system through armed resistance and radical self-transformation”.[17]

Total liberation, then, is both a conceptual framework with which to dismantle social constructs that reinforce domination, such as white supremacy and the human/animal binary, and a method, choosing resistance, prefigurative politics and direct action over lobbying and policy measures. For example, the Animal Liberation Front, a decentralized movement emerging from the UK in the 70s and an inspiration for total liberationists, has clear guidelines for whomever wishes to claim membership to an action cell. You’d have:

- To inflict economic damage on those who profit from the misery and exploitation of animals.

- To liberate animals from places of abuse, such as laboratories, factory farms, fur farms etc., and place them in good homes where they may live out their natural lives, free from suffering.

- To reveal the horror and atrocities committed against animals behind locked doors, by performing nonviolent direct actions and liberations.

- To take all necessary precautions against harming any animal, human and non-human.

- Any group of people who are vegetarians or vegans and who carry out actions according to ALF guidelines have the right to regard themselves as part of the ALF.[18]

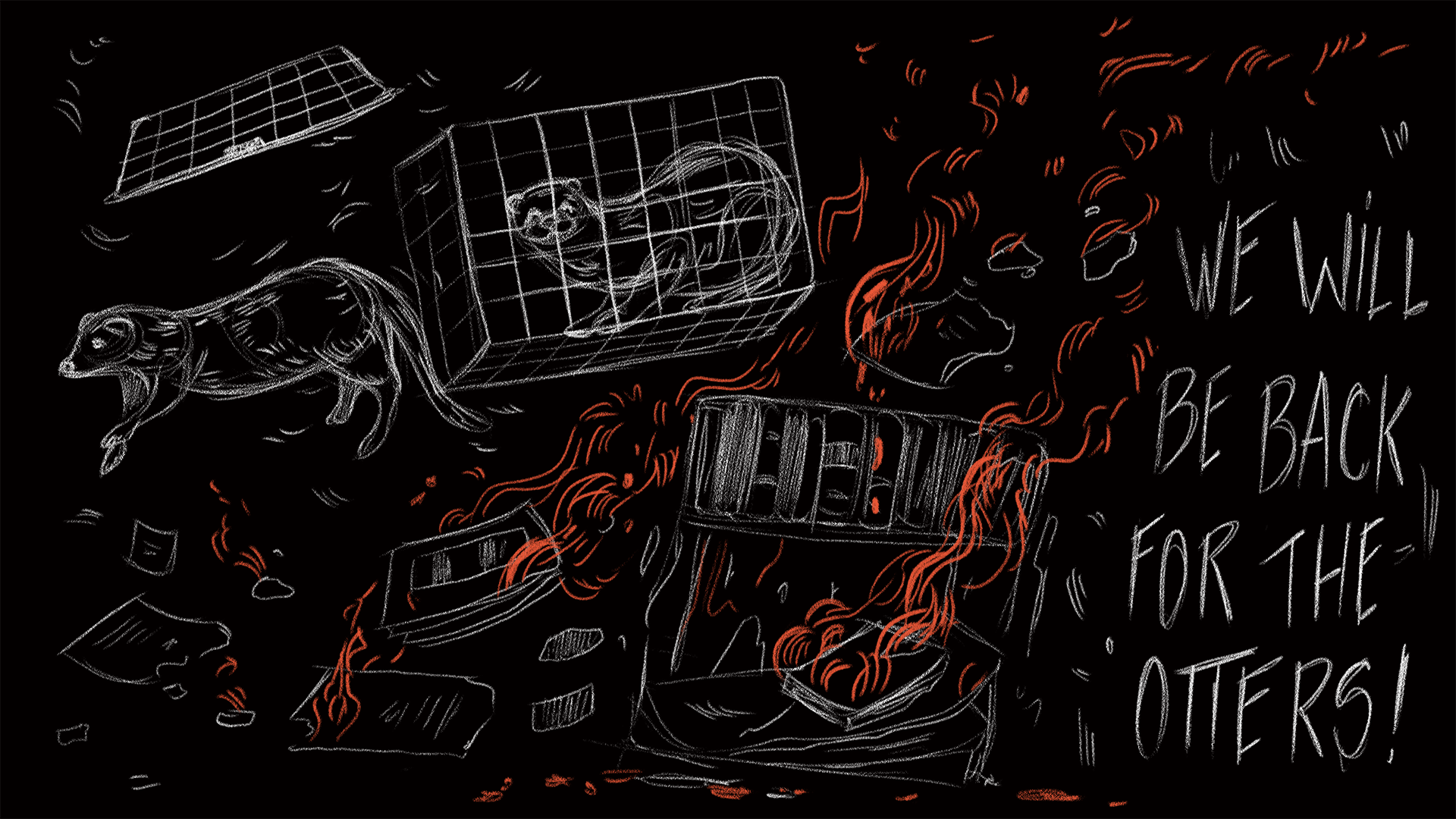

You can see from these very few rules how the ALF doesn’t wait for the state to decide whether other animals matter or not: they treat them as persons with subjectivity by acting towards their freedom, even if it means putting themselves in danger. Rod Coronado, an Indigenous American animal and environmental liberationist, who was involved in anti-fur operations, said:

“We have no obligation to any government. We have every obligation to protect the earth that gives us life and our future generations. Adherence to laws that sanction the destruction of our one home planet are crimes unprecedented in human history and demand active refusal and resistance”.[19]

His acts were part of the multi-phase Operation Bite Back, an ALF campaign targeting the American fur industry in the 90s.[20] It caused serious economic damage to the fur industry which was structurally torturing minks and otters. So much so that the Animal Enterprise Protection Act was amended, a law meant to criminalize the damage of any animal enterprise property.

You see, what states do?

All ideas have a history, a standpoint. As such, the total liberation framework came especially as a response to animal rights and environmental movements who kept elitist, patriarchal, racist and homophobic elements of society unquestioned.[21] As for anything born in such an oppressive context, these “omissions” weren’t unlikely. The animal rights movement is not the first to “forget” about issues it doesn’t directly tackle. Maybe the worst is when environmental and animal movements have fallen into ecofascist rethorics, misdirecting blame from the structural exploitation of resources to racialized groups. But even good intentions can go awry: when animal rights activists uncritically make comparisons between animal exploitation and the enslavement of Black people, for example, it can be seen as a way of superficially appropriating struggles and re-inscribing animality upon the Black body.[22] If the Black struggle is to be looked at as an example, it can be through direct working together in mutuality, as Angela Davis calls it.[23] Just like anti-carceral activists did when they noticed the FBI working against both movements with similar tactics, classifying Assata Shakur a “domestic terrorist” around the same time as they were launching Operation Backfire against the ALF and ELF.[24] Seeing commonality in their struggle, they created cultures of resistance to state repression. More specifically, when understanding that both animal liberationists and Black activists were being targeted by the FBI and incarcerated, they started creating networks of prisoner support across movements. Pellow notes that these include the “Black Panther Party, the Black Liberation Army, anti-Nuclear/Peace movements, Puerto Rican Independentistas, the Zapatista National Liberation Army, the American Indian Movement, and Indigenous resistance movements in Latin America”. Activists also engaged in criticism of the discourses of “ecoterrorism” and, to protect themselves, started practicing “security culture” more seriously. Ultimately, state repression in the US seems to have made it clear to different movements that they needed to work together. [25] Maybe that’s a good table to sit at? The one in which, beyond fear and difference, you break bread, share strategies, learn to survive together.

There is much theoretical work still to be done to understand how being considered “closer” to animality affects various groups of marginalized or racialized peoples, as human supremacy is always articulated for one specific kind of human, not for all.[26] As Black philosopher Syl Ko notices, we have to focus on how this “human” figure is articulated in the first place, realizing it’s not about putting the concept of species or race into our analysis forcibly, but analyzing how they were always already entangled.[27] And yes, there is even more work to be done on the ground, building these networks of mutual solidarity across movements, differences and borders.[28]

So, what’s holding us back from setting that broader, longer, sinuous table? Is the task too great, maybe? Should we start… smaller?

Despite its grasp on much of the Western world’s imagination, most people don’t live in the US. If we are to accustom total liberation to our own spaces, we “must always prize a diversity of tactics and perspectives”.[29] As an anonymous writer says:

“The essential ingredient is merely that legal and illegal projects maintain strong ties with one another, thereby providing communes on the front-line with the support needed to go further, all the while maximising the level of involvement achieved by safer options.”[30]

Steven Best, as well, provides a scathing critique of fundamentalist pacifism, considering that it belittles a movement’s powers and cuts its possibilities. Seeing reality as “ambiguous, paradoxical, dilemma-ridden, and often undecideable” he advances a “a pragmatic, contextualist, and pluralist method (…) that maximizes the possibilities for struggle and progressive change.”[31]

Analyzing previous movements successes and failures, the anonymous writer of the pamphlet called “Total Liberation” notices that anarchistic movements are harder for the state to repress, as anyone can be part of a direct action cell, and few people can inflict a lot of economic damage if they so wish.[32] However, they caution us to ask – what happens after an insurrection? They say we need “Some kind of assurance revolution won’t be the death of us.”, aiming to answer the question posed by many of those who don’t believe in total liberation: what will we put in place of the system we already have? It makes many of us suffer, some more than others, but it’s here. It works, for some. For others, it brings a lot of advantages. What would they possibly give them up for? They write that:

“Pushing the boundaries of struggle means establishing viable routes of desertion from the system, both accessible and secure. In short, anarchy expands by making it liveable.”[33]

This is where prefigurative politics comes into play. We can lend our bodies with grace to the slow work of the daily. We can attempt to care for diverse life and to sustain kinships beyond species, as Angela Balzano calls for, following Donna Haraway.[34] There are many unheroic tasks that build up to stronger communities, from peeling potatoes for a Food Not Bombs initiative, wheatpasting posters for a mutual aid fund, tending to a communal garden’s plants, carrying compost from here to there, to organizing DIY workshops, tool libraries and much more. You’ve seen them around, they’re not unusual or hard to do. As soon as we see them as part of a network of building alternatives to the capitalist state system, we gain a glimpse of how we could do things otherwise. A tiny glimpse, that is. Perhaps too tiny? Barely a candle on a table surrounded by laughter and friends. With perhaps a dog napping nearby. No owner in sight. Just a cat, cuddling next to him.

Take a seat. Are you more comfortable now? Or rather worried? Are you more hopeful, or just as hopeless? Oh, yes, we have to unmake and unmake and unmake… until we can make something new. And, yes, we make while we unmake too, like rivers, we learn when to flow and when to chip away at the obstacles in our paths. When to burst and break, when to change and nourish. We speak and act in praise of the slow work of survival amidst chaos, trying to build our dreams while the world goes to ruin.

Take strength from the figures of resistance fighters everywhere, from Ferguson to Palestine, Rojava to Chiapas, South Africa to Algeria, Haiti to Philippines, Brazil to Spain and much more.[35] Think, too, of animal rebels, individuals whose stories are narrated by Jason Hribal, Sarat Colling, the Resistenza Animale collective and others.[36] For a start, take Camilla, a cow who escaped a small farm in Tuscany, lived in the woods until being found again, imprisoned… and only after much pressure, finally liberated. Imagine, for a moment, what it might feel like to wander the forests for the first time, the sun’s light scattering playfully as the leaves crumble under heavy hooves. As antispeciesist activist Marco Reggio writes, the first part is to really notice the other with whom we are to be in solidarity. Without paternalism, without asking that they speak like we do.[37]

In the case of non-human animals, veganism is just one small step towards recognizing their full personhood and dignity. Many more need to be taken towards total liberation, for total liberation is a walk on an open path, endlessly forking into new directions. It’s not just about the liberation of those like you, and not just about the liberation of non-human animals. That would be impossible. It’s all entangled, remember? But fear not, you are not alone on this path. We will often stop to dine when we tire, as friends, comrades and companion species. Both to laugh, and to cry. To replenish our forces. To dream, to organize, to create and to work towards liberation.

Until this table will rot into the Earth. Until we, too, become soil again.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Andrea Penso and Eva Meijer for allowing us to include musical compositions and tracks from their albums.

Special thanks to Raluca Panait, Nóra Ugron & G for the kind suggestions on the text.

This video received a small grant in 2024 called the “Jen Angel Anarchist Media Grant” from Agency and the Institute for Anarchist Studies for which we’re very grateful! We’re also incredibly grateful to all our patreons who continue to support us and without which this video would not have been possible.

Notes

[1] Much of this essay is based on David Pellow’s book. See David Naguib Pellow, Total Liberation: The Power and Promise of Animal Rights and the Radical Earth Movement (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014).

[2] Angela Y. Davis, Freedom Is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement, ed. Frank Barat (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2016).

[3] Many feminists and especially feminist socialists have written about how essential reproductive labour is, a form of labour often done by women and feminized others. Our reference here is Angela Balzano. Angela Balzano, Per farla finita con la famiglia: Dall’aborto alle parentele postumane (Rome: Meltemi Editore, 2022).

[4] Greenpeace, “IKEA Furniture Destroys Some of Europe’s Last Remaining Ancient Forests,” press release, July 1, 2021, https://www.greenpeace.org/international/press-release/66349/ikea-furniture-destroys-some-of-europes-last-remaining-ancient-forests/.

[5] Environmental Investigation Agency, “IKEA’s Romanian Wood Sourcing Woes Highlight the Need for National Transparent Timber Traceability Systems Across Europe,” EIA Blog, March 15, 2021, https://eia.org/blog/ikeas-romanian-wood-sourcing-woes-highlight-the-need-for-national-transparent-timber-traceability-systems-across-europe/.

[6] Pellow.

[7] Flower Bomb, “Infinite Bloom: Anarchy Beyond Human Supremacy,” in Veganarchism: Making Veganism and Anarchism Dangerous Again, ed. Will Boisseau and Nathan Poirier (Active Distribution, 2024), 48.

[8] These are some examples we came up with, but to read on how states tried to order the natural and social world, you can check out James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998).

[9] Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser, “Meat Production,” Our World in Data, accessed May 30, 2025, https://ourworldindata.org/meat-production; Grand View Research, “Vegan Food Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report by Product, by Distribution Channel, by Region, and Segment Forecasts, 2021–2028,” accessed May 30, 2025, https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/vegan-food-market.

[10] The following article notes this in a critical manner: Lundström, Markus. “The Political Economy of Meat.” Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 32, no. 1 (February 2019): 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-019-09760-9.

[11] Following Balzano’s question of how to (re)produce differently, after asking “what do we produce that harms the other?”. Balzano, Per farla finita con la famiglia: Dall’aborto alle parentele postumane. For an English review of the book, see Maria Martelli, „Multispecies tunes to making kin, not reproducing capitalism”, Posthum Journal https://posthum.ro/recenzii/maria-martelli-multispecies-tunes-to-making-kin-not-reproducing-capitalism/.

[12] Anonymous, Total Liberation, 2nd ed. (London: Active Distribution, 2019) 34.

[13] Oscar Heanue, “For Slaughterhouse Workers, Physical Injuries Are Only the Beginning,” OnLabor, January 17, 2022, https://onlabor.org/for-slaughterhouse-workers-physical-injuries-are-only-the-beginning/; For more connections between disability and animal liberation, see Sunaura Taylor, Beasts of Burden: Animal and Disability Liberation (New York: The New Press, 2017).

[14] Pellow.

[15] Steven Best, The Politics of Total Liberation: Revolution for the 21st Century (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 69 (ebook version).

[16] Roger Yates, “TOTAL LIBERATION: A HOLISTIC APPROACH TO HUMAN, EARTH, AND ANIMAL LIBERATION (H.E.A.L.) ,” YouTube video, 1:23:45, May 15, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cj5-R69WKVw. This is an interview with Laura Schleifer. Importantly, she also mentioned that the TL framework is influenced by “Critical Race Theory, Queer theory, Ecofeminism, Decolonization, Deep Ecology, Social Ecology”, and many others, to which I would add mad studies, disability justice and children’s liberation.

[17] Speaking of the United States, the authors also note, following Assata Shakur, that “economic dependency on a neocolonial system is pseudo freedom”. Sarat Colling, Sean Parson, and Alessandro Arrigoni, “Until All Are Free: Total Liberation Through Revolutionary Decolonization, Groundless Solidarity, and a Relationship Framework,” in Defining Critical Animal Studies: An Intersectional Social Justice Approach for Liberation, ed. Anthony J. Nocella II et al. (New York: Peter Lang, 2014), 51–73.

[18] Anthony J. Nocella II et al., eds., Defining Critical Animal Studies: An Intersectional Social Justice Approach for Liberation (New York: Peter Lang, 2014). We advise you to check other collections by Nocella as many touch on the theme of total liberation.

[19] Pellow.

[20] For more on this, see Cahill, Eileen, “‘Operation Bite Back”, 2024, https://bangsirieomma120.substack.com/p/operation-bite-back-review and Rod Coronado’s own account from prison “THE FIRST TIME I SAW A FUR FARM:” http://sisis.nativeweb.org/sov/rod1fur.html.

[21] Pellow.

[22] Pellow. For further reading, important work in analysing the racial politics of animality is done by Claire Jean Kim.

[23] Davis.

[24] Pellow.

[25] Pellow.

[26] The field of feminist and critical posthumanism argues this incessantly, but so do critical animal studies and some decolonial frameworks.

[27] Syl Ko, “We can avoid the debate about comparing human and animal oppressions, if we simply make the right connections,” in Aphro-ism: Essays on Pop Culture, Feminism, and Black Veganism from Two Sisters, by Aph Ko and Syl Ko (New York: Lantern Books, 2017), 87.

[28] The author has written more about solidarity in: Nóra Ugron, Martelli Maria & Popovici, Veda. “Relationality, Not Universality: A Dialogue on Solidarity Across Movements, Borders and Species.” Vol. 10 (2025) Matters: Journal of New Materialist Research, https://revistes.ub.edu/index.php/matter/article/view/49358.

[29] Anonymous, 68.

[30] Anonymous, 86.

[31] Best.

[32] Anonymous. Support for direct action also comes from the more recent book on climate resistance by Malm. See Andreas Malm, How to Blow Up a Pipeline: Learning to Fight in a World on Fire (London: Verso Books, 2021).

[33] Anonymous, 95.

[34] Balzano.

[35] From Ferguson to Palestine is taken from Angela Davis’ book titled “Freedom is a constant struggle”, pointing to the connection of the Black liberation struggle—after the murder of Michael Brown—to the liberation of the Palestinian people from Israel’s colonial occupation and genocide. Rojava refers to the Revolution that has been going on for more than 10 years in what is now known as the Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria; while Chiapas is the geography in which the decentralized, rebellious Indigenous peoples and anarchist-like Zapatistas reside. The end of apartheid in South Africa necessitated decades of resistance, while Algeria had its war of independence from France in which anarchists were involved as well. The Haitian Revolution is known as an early anti-colonial uprising, and the Philippines had its own anti-colonial struggle in which anarchists participated. Anarchism in Brazil has a long history, particularly in the labour movement, while Spain is known for the CNT and the Revolution of the 30s, when workers took over land, seized the means of production, and implemented society-wide democratic decision making processes. Of course, these are just some examples. Luckily, the list is much, much longer.

[36] See Sarat Colling, Animal Resistance: Challenging the Boundaries of Speciesism; Jason Hribal, Fear of the Animal Planet: The Hidden History of Animal Resistance (Oakland: AK Press, 2010); Resistenza Animale, accessed May 30, 2025, https://resistenzanimale.noblogs.org/ as well as our previous video-essay: just wondering, 2024, “Escape, Resistance and Solidarity – Farmed Animal Sanctuaries as the Heart of the Movement –” directed by Aron Nor 37’18 https://justwondering.io/escape-resistance-and-solidarity/.

[37] The entire story of Camilla is recounted by Reggio. See Marco Reggio, Cospirazione Animale. Tra azione diretta e intersezionalità. (Rome: Meltemi Editore, 2022).