Animal & Disability Liberation

with Sunaura Taylor

I. this fable is not for your inspiration

There was once a fox whose bones were curved at the joints. He used to keep his belly full and hunger at bay. His walk was unusual, but he was strong and a good hunter. In this fable, the fox doesn’t get to be cunning. In this fable, the fox is shot by a well-meaning human, who, seeing his abnormal gait, feels mercy! and takes pity! and goes on to destroy this life considered not-worth-living. In this fable, someone dies because of what someone else thinks is a good body, a body that can sustain itself in the world.

You don’t usually hear of diseases like arthrogryposis in fables. And yet they exist, side by side with medical models of what is considered healthy. They don’t stop at our species only. This is not just a fable. The fox was alive, and then he was killed, out of mercy. So, why did this happen?

[Image description: On a black background there is a drawing of a fox with arthrogryposis (curved joints) in simple white and orange lines.]

II. disabled bodies and ableism

Sunaura Taylor is an artist, writer and activist for disability and animal rights. She was born with arthrogryposis, which was simply her embodiment. But later, as a child, when she couldn’t dance like other kids, she realized something was different about her. Kids can be mean, and they would call her “monkey”... which was supposed to be an insult, so she felt it as such, although actually, she loved monkeys.

In her book, “Beasts of Burden”, Taylor draws some lines of connection between two movements which have been at odds: animal rights and disability rights. So let’s start with what bodies can and cannot do. There are two main models of disability: the medical model and the social model. The medical model sees disability as something to be “fixed” and cured, something that is a matter of the individual body, a body that defies norms of health in negative ways. The social model, on the other hand, takes a broader view of disability, pointing to how it is enmeshed into the social and material environment, and that it is not purely a matter of curing the individual, but of organizing society. The social model doesn’t deny there might be a need for doctors or medicine, but it stands to say that access is a question of justice, and that disability is often given by how the environment is shaped.Imagine if we had more ramps, instead of stairs, more braille instead of latin alphabet, more sign language instead of oral language - none of these ways of moving and communicating are more ‘natural’ than the other, but they are more advantageous for some abilities rather than others.

As people living in ableist societies, we’ve most probably thought in ableist terms without even realizing. So...What is ableism? It is prejudice against disabled people, and it carries suppositions of what they can do and what their lives can be like. It can lead to discrimination, such as lack of access to jobs and education, and it breeds systems of oppression that value one form of embodiment over another. Disability rights activists have worked a lot to challenge ableism in many ways, including showing how disability can foster other, creative ways of knowing and being in the world. Bodies are surprising, and they can act in various ways, not just what we’re accustomed with. Disabled people have often surprised the medical community not only with living longer than predicted, but also with having better, richer lives, defying standards of what is possible and desirable.

[Image description: On a black background, a portrait of Sunaura Taylor smiling, drawn in white lines. On her right side, a manatee in green lines and around her, baby chicks in white, green and orange lines, in many diverse positions and embodiments.]

III. animal and disability liberation are entangled

What does all of this have to do with non-human animals? Well, there’s a catch. Disabled people have often been demeaned and considered less worthy because of what they can and cannot do, being sometimes compared to animals, thus ‘animalized’. This carries a huge risk to their lives, as nonhuman animal lives are, most of the time, considered disposable. In her book, Taylor is trying to argue how, following the way ableism organizes the worth of lives and of bodies in connection to their capacities, animal and disability liberation are entangled. Animals are often considered less worthy because, according to (hu)man norms and environments, they are less capable. They do not speak human languages perfectly nor do they engage in mathematics to a high degree. Therefore, it is not only disabled humans who suffer from ableism, but non-human beings, as well.

This comparison carries weight. One might breathe in. When making this argument, Taylor was accused of comparing herself to an animal, of degrading herself, as if she was not having enough disability pride and acceptance for her body. She answered carefully that she is actually pointing to the source of oppression: ableism as a mechanism of valuing some capabilities and not others, and of ordering even the worth of lives based on that.

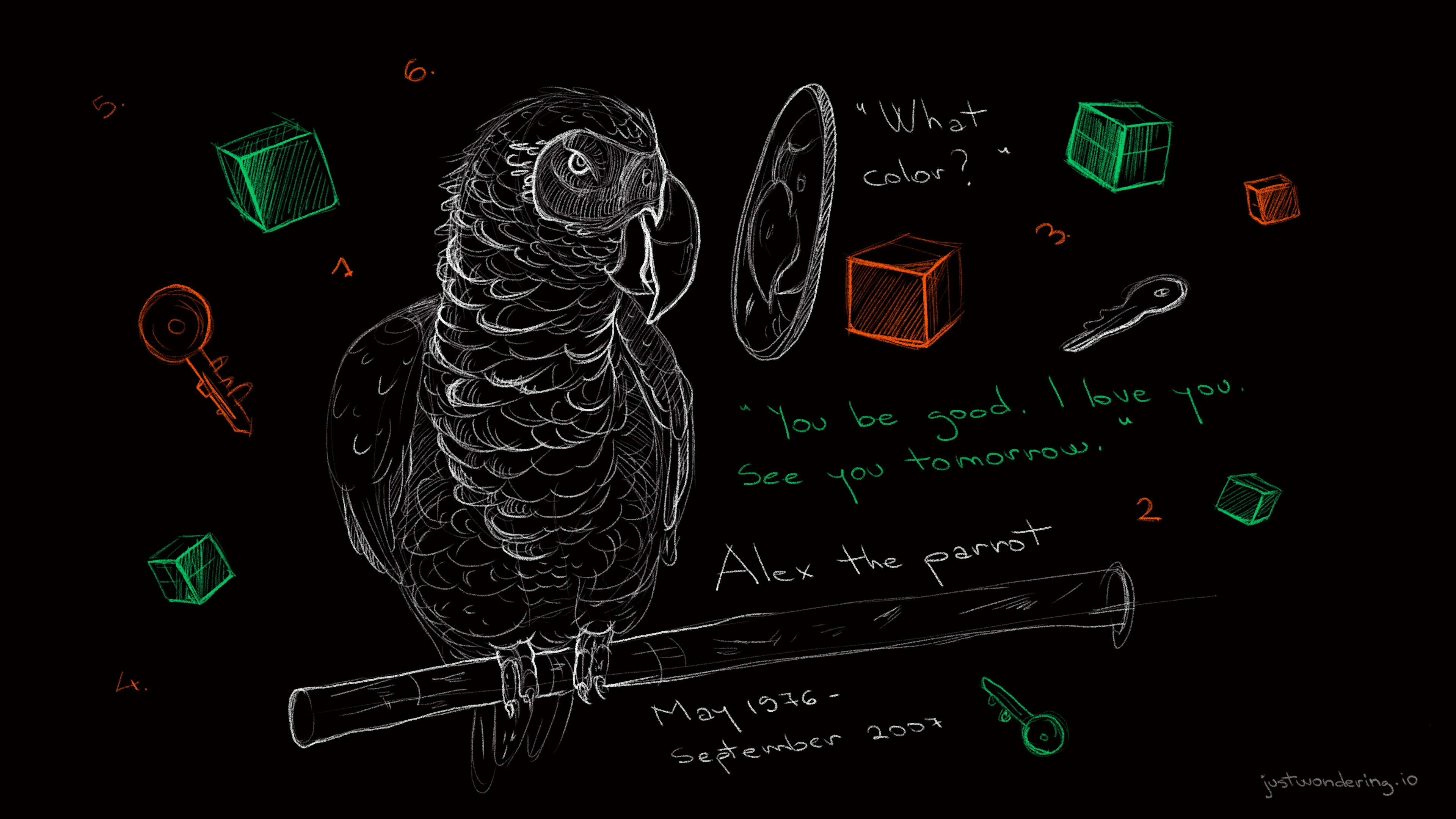

[Image description: On a black background there is a drawing of a parrot in white lines, at the center of the image. He is standing on a stick, and above it his name is written: Alex the Parrot. Below, the time of his life (May 1997 - September 2007). Above his name, in green lines, a quote of his last words: “You be good. I love you. See you tomorrow.” Cubes and keys, drawn in orange and green lines, float around him. Next to his face, there is a mirror, and near it another quote from him: “What color?” is a question he asked, referring to himself while looking at a mirror.]

However, she thought, why should it be so terrible to be compared to an animal anyway? This judgement relies heavily on speciesism, the belief in human superiority over other animals, which ends up justifying the use of nonhuman animal bodies and the domination over their lives. Speciesism allows us to take animal lives simply because they are not human. But, as many writers have shown, it can always be used against humans, as: “to call someone an animal is to render them a being to whom one does not have responsibilities, a being that can be shamelessly objectified”.

Sunaura Taylor then asks us: “What if instead of demeaning us, claiming animality could be a way of challenging the violence of animalization and of speciesism—of recognizing that animal liberation is entangled with our own?” So she does just that in her many painted self-portraits with bisons, bears, pigs and other nonhuman animals. But she is cautious, she knows this risk is not easy for everyone to take up. As a white woman who had access to education, Taylor highlights that closeness to animality might come painlessly to her, without a terrible cost. However, it is not being animal that scares us so much - humans are, after all, animals - but the dehumanization and objectification that comes with it. These are not abstractions: we must recognize entire histories of racist, ableist and sexist exploitation and oppression justified by claiming similarity with “the animal”. Just remember that there were such things as zoos which imprisoned human beings for show. And that now, there are, still, zoos that imprison nonhuman beings, some of which give them antidepressants to help them cope with living in captivity.

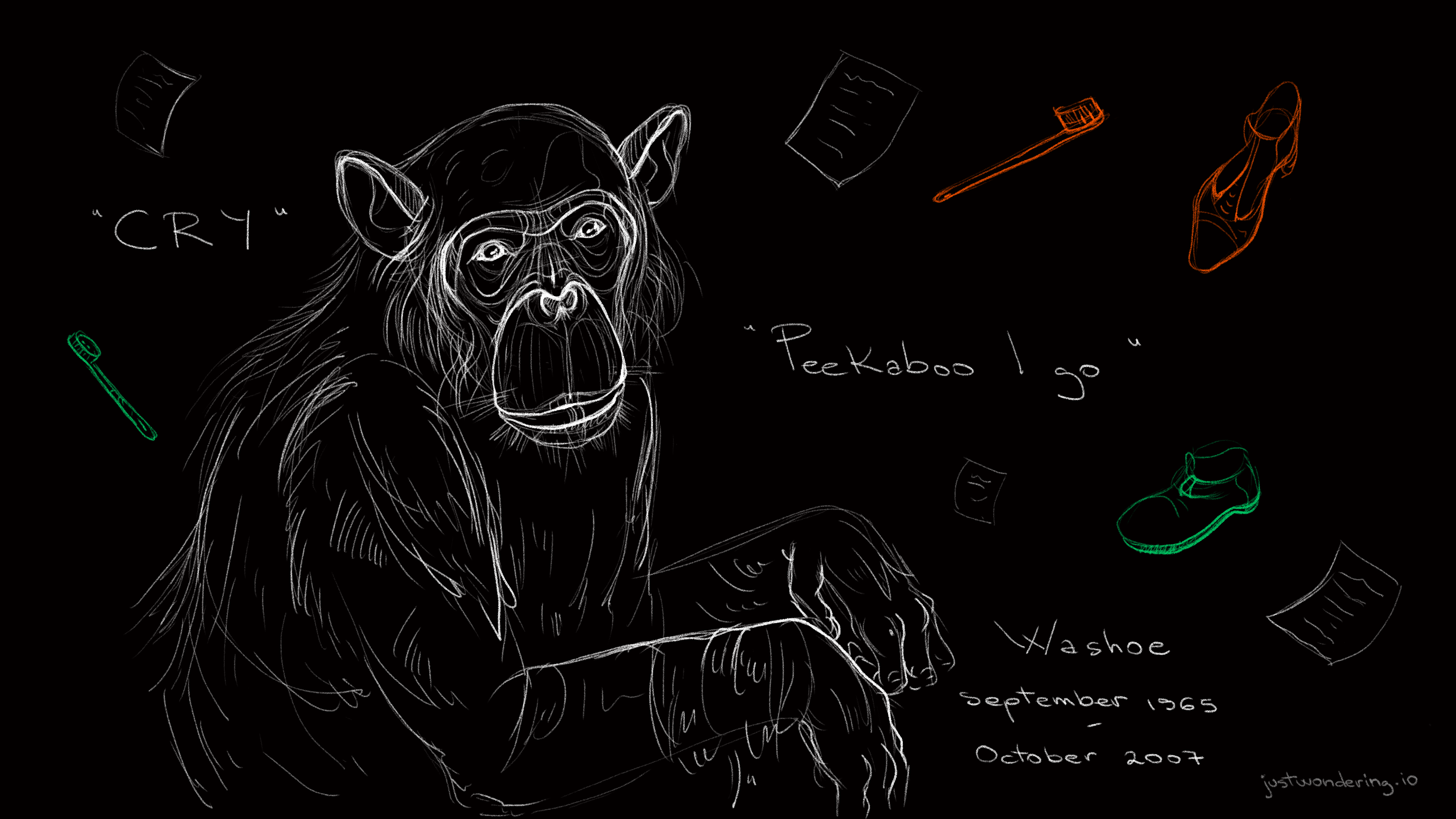

[Image description: On a black background there is a drawing of a chimpanzee in white lines. Next to her hands, her name and life period: Washoe - September 1965, October 2007. On her right, written in white lines, is something she said to a researcher “Cry” and on her left, something else she said “Peekabo I go”. Toothbrushes, papers and shoes are floating around, drawn in orange, white and green lines.]

IV. cripping animal ethics

Have you ever tried to count, listen to or look at an entire truck of chickens packed for slaughter? Paid attention to every individual life, or given them an ounce of your time? Working to complete a large painting of a truck crowded with chickens, Taylor realized farmed animals are bred to be disabled. Their disabilities, or ‘super-abilities’, are selected to better cater to the market: in the meat industry, chickens are bred for their huge breast, which causes skeletal malformation; in the egg industry, chickens are bred to lay hundreds of eggs a year, as opposed to their normal dozen, which causes reproductive problems. In this capitalist economy and probably, in any other anthropocentric growth-based economy, animal disability is profitable and desirable. Yet, if we were to abolish such consumption, how would these nonhumans live, given that they, at least partly, depend on humans for survival? Taylor suggests that the animal rights movement has much to learn from disability studies, as it is not only that ability should not determine the right to live, but neither should being dependent.

“Dependency has been used to justify slavery, patriarchy, imperialism, colonization, and disability oppression. The language of dependency is a brilliant rhetorical tool, allowing those who use it to sound compassionate and caring while continuing to exploit those they are supposedly concerned about.”

Learning an ethics of care, and realizing we are all, to certain degrees, dependent on each other, is a good, humbling start at working towards better lives for us all. Moreover, realizing how power works, and how oppression operates, is helpful in our many fights for justice.

“When animal commodification and slaughter is justified through ableist positions, veganism becomes a radical anti-ableist position.”

Taylor proposes a “social model of veganism”, in recognition of the fact that some of the challenges to practicing veganism are not just personal, but structural. Some people have little control over their food choices, others live in food deserts or nursing homes.

“Cripping animal ethics means acknowledging that veganism as a diet is not as easy for some as it is for others, but that there are countless other ways one can challenge anthropocentrism, speciesism, and violence against animals. You can avoid animal products in other arenas, raise awareness about the violence of animal industries, participate in movements for animal liberation, protest the systemic economic exploitation of nonhumans, and you can bring an intersectional animal liberation framework into your other activist work.”

Thinking courageously requires being able to grasp contradictions and difficulties. Seeing veganism politically, as a radical stance against oppression, has to manifest beyond just changing habits to avoid the use of nonhuman animals - although that, too, is necessary. There is no reason to claim the difficulty of access others have to justify one’s own consumption of nonhuman animals.

We must acknowledge how being ‘animalized’ and thus objectified is hurtful and even deadly for some human beings, as well as it is hurtful and deadly for nonhuman beings, too. We should challenge the idea that some ability gives life more worth or value, in human and nonhuman animals alike. We are to tread lightly, this is fraught territory. Yet liberation can only be achieved commonly - if one axis of power remains untouched, it will come back to hunt and dominate us.

So let us work for a world in which foxes live freely outside of human fables. A world in which other animals are not farmed and bred to be disabled for human benefits, nor are they used and objectified. A world that can grasp complexity, that can cherish difference and honor caring. Let us strive to live in this world, where we act against disabling environments while truly valuing disabled lives.

[Image description: On a black background, a drawing of two chickens, mid-picture, in white and orange lines. The landscape is filled with curved roads, ramps, patches of grass and green spaces, various paths of mobility and accessibility. They are in the middle of a road that leads to a green tunnel.]

References:

Taylor, Sunaura (2017) Beasts of Burden: Animal and Disability Liberation, New York: The NewPress, ISBN: 9781620971284

Reviews:

Vettese, Troy (2017) Review of Beasts of Burden https://radicalantipode.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/book-review_vettese-on-taylor.pdf

Taylor, Chloe (2017) Cripping Animal Ethics. Review of Sunaura Taylor, Beasts of Burden https://animalliberationcurrents.com/cripping-animal-ethics/

Gressel, Madeline (2017) Interview with Sunaura Taylor https://www.bookforum.com/interviews/bookforum-talks-with-sunaura-taylor-18023

Videos:

A priviledged vegan (2018) How ableism hurts animals https://youtu.be/SxBqoqH6RWE

Earthling Liberation Kollective interview with Sunaura Taylor (2014) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Tj0Us8ySAE

Credits:

Written by M

Writing suggestions by Aron Nor

Recorded by M & Aron Nor

Illustrations made by Mina Mimosa

Video & Audio editing by Aron Nor