Straying home. A film essay with urban animals

Film transcript

Living in a post-industrial city in Romania, I have contact with different non-human animals in public spaces. Despite the rapidly modernizing urban landscape, some of them are still here. There are many birds such as crows, pigeons, sparrows and tits, but also other animals who share their territories with me. In the night, I see dogs passing the crosswalk and during the day, I see neighbouring cats jumping over fences. And there are many other animals I don’t notice, who are smaller or better at hiding.

whether you see us

whether you know us

whether you like us

or you despise us

this place you call home

is our home too

Part I

– “problem” animals –

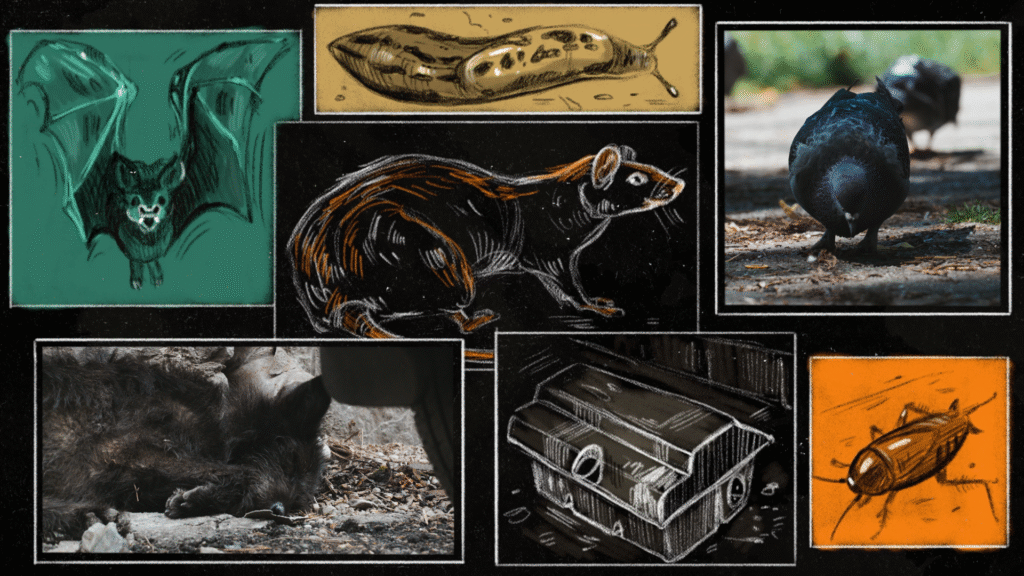

The modern city is unkind to many liminal animals, unfortunately, and they struggle to find a place in it. In the touristifying landscape where I live many of them are framed as a “surplus” in need of control. Configuring them as such happens when certain aspects of their existence are highlighted only to be essentialized as problems, while others are invisibilized.[1] So, on one hand, different normal and natural processes such as moving, breeding, and defecating, are problematized. On the other hand, their cultures, social bonds, and individual experiences are erased from view. In this way, from co-inhabitants of the land, urban animals become “dirty”, “dangerous”, and “useless” beings. As Claudia Hirtenfelder points out in her work, they are constructed as “problems” in need of regulation.[2] These configurations are shaped by power relations spanning across societal norms, economic interests, and human values. And they are a way of fabricating particular anthropocentric urban natures through the violent negation and erasure of others.

The sight of a cat in heat, pigeons defecating, and—perhaps the most scorned of all—rats running loose, are all viewed with disdain. Many urban animals are seen as “dangers” to be dealt with and as “hazards” to humans, to buildings, to Nature, and sometimes even to themselves.[3] There’s rarely a place for them in the visions put forward. They either become “pests” to be eradicated or “pets” to be owned. Within contemporary industrial-capitalist systems, non-human animals who live around us are generally regarded as impediments. They become risky and menacing obstacles to human and capital development, or, in a romanticized view of it, to Nature. So, speaking of them as “vermin”, “pests”, or “strays”, is both a historical and a political matter. It is a matter of constructing these animals specifically as “problem” animals.[4] In this way, urban animals become governable.[5] They can be subjected to control, discipline, containment, and eradication. Thus, the “civilizing” quest to determine who belongs where and to purify the city of its more-than-human inhabitants can be carried out.

Part II

– one way to look –

There are still other ways of looking. One of the reasons urban animals are so often seen as transgressive and criminal has to do with the fact that their ways of living are denaturalized. So, understanding their social and territorial relations differently is important.

Think of pigeons and dogs. They seem totally different, right? Still, pigeons and dogs can be somewhat alike.[6] When residing in an urban setting, adapting to it for a longer period of time, both can be thought of as living in a synanthropic or commensal relationship. These two terms can be used interchangeably when referring to animals who live in urban areas or around human structures. But there are also nuances.[7] A synanthropic relationship points to animals who live close to human settlements, adapting to the anthropic landscape.[8] However, a commensal form of living can reveal something particular within the former relationship.[9] It can point to animals who benefit or rely on discarded food scraps from humans, and not simply to those who live around us unbothered by the proximity.[10]

When scavenging for food in our immediate surroundings, both some pigeon and dog populations can be seen in this way.[11] Seeing them differently is also a matter of understanding the malleability of terms such as domestic, wild, and synanthropic. As Terry O’Connor argues, these labels are more properly applied when they refer to particular animal groups, not when they are utilized at the species level.[12] When considering sheep and wolves side by side it is easy to assume that some species are domestic and some are wild. However, thinking of pigeons undermines this logic. They show us that these categories only make sense at the population level, not at the species one.[13] It is the relationship that matters.[14] Depending on the context, pigeons may be considered domestic, as homing pigeons, but also commensal scavengers in urban environments, or even wild animals, when living as self-sustaining rock doves.[15] O’Connor points out that in some places, such as north of the European Alps, it’s also hard to tell wild from commensal populations.[16] When you think about it, there is no reason to assume that this fluidity applies exclusively to pigeons. Other animal populations also vary across the globe and they can blur rigid classifications at the species level. The differences between how they live and relate to humans, challenges us to think more thoughtfully about how we end up describing them.

Let’s consider dogs. Dogs’ evolutionary history is not as straightforward as one might think. Contrary to what is generally assumed about domestication, different theories seem to show that wolves acted more on their own terms. According to a well-known theory, it all began when wolves started scavenging human scraps from refuse dumps.[17] It is believed that these self-taming wolves evolved into dogs through a process of natural selection, by adapting to the new ecological niche unknowingly created by humans.[18] But there are other stories too about “how dogs became dogs”, and some of them criticize this narrative.[19] By drawing from indigenous accounts some authors have pointed out the opposite, that humans might not have been able to pull it through without scavenging kills made by wolves.[20] Their theory stresses how indigenous peoples saw wolves as teachers and guides and speaks of the cooperative aspect of their relations.[21] From this perspective, domestication is thought to have resulted from a coevolutionary relationship initiated by wolves.[22]

By only thinking about how they live in contemporary societies in the Global North, it is easy to overlook that for a very long time dogs moved relatively freely up until the 19th century even in the West.[23] And also that, on a global scale, most of them still do.[24] Over the last two hundred years, dogs in public spaces have increasingly become a symbol of cultural “backwardness” for self-proclaimed “civilized” cities in the West, as historian Chris Pearson shows.[25] Yet, even today, not everyone shares this perception, and it was never universally held.[26] The view that dogs should be strictly controlled and not allowed to move freely – born within the metropoles of imperial and colonial powers – spread from Western Europe and North America to other parts of the world.[27] This view continues to mold their lives and our relations with dogs in many places today. Still, dogs who are confined in a human home, and are reproductively controlled, are a minority worldwide.[28] While most dogs in the West are strictly restrained nowadays, in other parts of the world dogs adopt a commensal lifestyle.[29] Thus, their populations can have different social and territorial relationships depending on how and where they live. Compared to “pets”, these dogs who can be seen as living in a synanthropic relationship are not directly dependent on humans. Nevertheless, since they live in human-altered environments, they may rely on specific features of the ecological niche.[30] This can include things like leftover food from humans or certain spatial configurations and cultural attitudes towards them.

Some animals who make the city their home have shared their territories with us for a very long time. Sadly, this does not spare them from human hostilities. While some storks, squirrels, or songbirds may be welcomed in different cities, many synanthropes are feared, ignored and profoundly hated.[31] Cultural attitudes play a huge role in how these liminal animals are perceived.[32] Rats, for instance, are typically framed in negative terms.[33] Thus, poison traps are scattered all over many of our cities. And they are not the only ones seen in a negative light. Bats, slugs, and cockroaches are regarded with disdain too.[34] And street pigeons and dogs, if not outright hated, can also raise people’s eyebrows, especially in the Global North, or in newly urbanized and gentrified places.[35] Thus, the topic of “overpopulation” dominates the discourse about them and about other non-human neighbours deemed a threat to the sanitized city.[36] Even when their populations are far from exceeding the limits of their ecological niche, or when they are shrinking compared to other periods, they are still objectified as a “surplus”. The interventions that target them are not usually or mainly aimed at caring for their quality of life, nor for their health, but at removing them or shrinking their populations, one way or another. That is the main objective.

Synanthropes are often blamed for different things, including for human-made ecological problems. And once the panic is set, it becomes harder for people to appreciate them as individuals or to see that synanthropes can play an important role in urban ecology.[37] Rats, for instance, could be involved “in preventing serious phenomena, such as the rotting of organic material, and thus in controlling the proliferation of microbes”.[38] And there was a time when street dogs, in some parts of the world, “were more than tolerated” for maintaining public hygiene through waste consumption.[39] Still, whether or not liminal animals are beneficial for urban ecology, they shouldn’t be seen only through this lens. After all, we should always question the idea that a being – human or not – is worthy only when others can benefit from them.

– another way to look –

The city automatically becomes a multispecies landscape when we challenge modern purified visions of it. Understanding some of our nonhuman neighbors as synanthropes positions them as co-inhabitants of the land, rather than as intruders. But how do we trouble the pejorative labels many urban animals receive? While synanthropes adapt to anthropic spaces, they also challenge humanist understandings. By acknowledging their agency, we can give a positive spin to the negative connotations affecting them. Speaking of urban animals as subjects who resist being controlled and who have plans of their own, rather than seeing them as objects of intervention, is an important aspect in doing justice to them.

Think for a moment about what it means to “stray”. This is a term that has negative connotations for cats and dogs. Depending on where you live you might have a clear picture of what “straying” implies. However, because legal practices and cultural understandings vary across the globe, it is never quite clear when a cat or a dog is “straying”. Seeing village dogs, or neighborhood cats, as “strays” is a way of marking them as a problem or as a mistake, something to be solved and fixed.[40] Whether they are seen as “unowned”, “undesirable”, “intrusive”, “lost”, or “abandoned”, “strays” are generally considered “unruly” animals in need of strict regulation. They are seen as transgressing their “proper” role and place in society, either by choice or human negligence. But what is their so-called “proper” place and role? The answer, of course, depends on whom one asks. Not only does it vary culturally, it varies with time, and from human to non-human animals. In Romania, for instance, cats and dogs who move freely outside the house are not necessarily seen as “strays” by everyone. While local understandings have been shifting fast in the last few years, freedom to roam might still be considered something normal or natural by at least some humans, which is rarely the case in most Western countries. So, what is “straying” all about if we understand it critically?

Let’s stop for a second to think about street dogs. Historical changes and cultural attitudes that lead to the widespread practice of “pet” ownership in the West, also shaped how dogs who moved freely came to be seen.[41] It was through comparisons with pedigree dogs that street dogs came to be perceived as “less evolved”.[42] As Chris Pearson shows, they were increasingly depicted in this way through an unsettling entanglement between dog breeding, racism, eugenics, and nationalism.[43] Similarly, their more autonomous lives became “less civilized” by comparison to those of “pets”.[44] From a Western perspective, free-roaming dogs came to be known as “strays”. They became governable entities to be removed from public spaces. Historical and cultural geographer Philip Howell calls the “stray” category nothing more but a “legal and spatial construction”.[45] The category itself refers to dogs who are rendered as “out of place”.[46] And it is shaped by its roots in colonial visions and understandings. Past and present attempts to “civilize” particular relations with dogs, at home and abroad, can make this visible. Dogs who are labeled as “strays” by tourists in different regions, may not, after all, be seen that way through other local understandings.[47] If we consider the diverse lives dogs have worldwide, the normality attached to certain practices of “pet” ownership becomes a sign of cultural imperialism.

Let me tell you a story about someone I know. Someone I like, and who likes me back. His name is Lăbuș. He is a dog from Romania whose mobility isn’t strictly controlled and who doesn’t wear a collar. Because of this, Lăbuș can be considered a “stray”. Authorities, tourists, and affluent neighbours – or resentful ones – could see him as such. Yet, by at least some local understandings, he is not a “lost” or “abandoned” dog, nor is he “unwelcome”. When he steps outside his yard, he becomes part of the neighborhood. While such views are casted solely in a negative light usually by those with economic privilege, older people might still share them.[48] Contrary to usual depictions of stray dogs on social media, Lăbuș is hearty, healthy, and happy. Not only does he have a reserved spot within a particular domestic space, he has humans in his life who care for him in various ways. Moreover, Lăbuș has a good understanding of the surrounding area. He crosses the street safely and avoids cars or humans who are not looking for interactions. Simply put, he knows how to take care of himself and steer clear of trouble.

Even before the elderly lady who cared for him moved, Lăbuș could be spotted outside from time to time. However, since her property became a construction site for a future house, the workers leave him outside more often. But this isn’t the only reason why Lăbuș can be spotted outside, which is sufficient enough to label him as “out of place”. He also willingly chooses to go out! He follows the workers. He greets the human and non-human neighbors in the region. And he enjoys resting on the sidewalk in front of the house. Aside from a few non-threatening barks signaling his presence, Labuș can’t be said to cause any disturbance to anyone. Yet, his existence could be marked as “disturbing”. And it can be depicted as such by people who know absolutely nothing about him or the neighborhood, which is his extended home and family.

Within capitalist urban formations, Lăbuș is just another case of an “improperly” and “irresponsibly” owned “pet”. As the human boundaries drawn around private property are no longer well defined, his status becomes unclear. He either becomes an “intruder” in need of correction or a “poor” dog who does not know what is best for him – which clearly isn’t the case. Different legal and spatial configurations mark him as a “stray” in need of control. How can we resist this dominant narrative? How can we do justice to him, as a subject?

A more politicized way of looking is to reframe the official discourse. This means seeing straying through a different lens.[49] For our human-centered institutions straying is something negative. But for Labuș, straying is a way of life through which he does not simply accept being pet-ified, commodified, and strictly controlled. So, from a non-anthropocentric activist perspective, straying can be subversive.[50] Rather than marking dogs, cats, or escaped and abused “farmed” animals as objects to be governed, it can draw attention to them as subjects with agency. Changing the meaning of words brings other experiences and realities forward.

Straying can also be thought of in more general terms. Within the prevailing discourse stray animals are regularly framed as perturbing public order. But human actions can also be criminalized when resisting the state’s power. So, straying can be seen as a form of defiance, connecting us politically with other animals. It can be an act of refusal to be assimilated or to be reduced to a prescribed social role. When we see it like this, straying takes on an entirely new meaning. It naturally becomes empowering rather than degrading.[51] Thus, its negative associations are transformed into a cross-species act of revolt. And seen through an expansive multispecies understanding of struggle, it becomes a way of moving beyond present imaginaries. Straying becomesa form of disobedience, a way of going against the status quo.

we’ve been standing & moving

don’t call us out of place

we don’t need you approving

we’ve always been here

this place you call home

is our home too

Part III

– changing relations –

We have seen how we can change the narrative. But how do we move from seeing urban animals differently to acting differently? It is not enough to understand their daily actions from a less anthropocentric angle, we need to actively take their agency into account to build more just futures. So, how do we live more justly together? Can we support urban animals in their projects while also taking into account the dangers of our exclusionary human-centered landscapes?[52] Is there a way to empower them not only to shape future political structures but also to challenge existing ones – without exposing them to more hostility and anthropogenic pressures?

These are complicated questions, and to complicate things even more, the answers cannot come solely from us. We need to consider different contexts and the urban animals we are trying to support in them. And we need to have exchanges with our non-human neighbours, centering their voices and ways of living, if we are to do justice to them.[53]

Reimagining present and future political communities with other animals is a challenging task. However, by drawing from the work of political theorists Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka we can understand urban animals as having their own self-governing political communities while also sharing a territory in common with us, and many other animals.[54] Doing justice to them would require us to find ways to coexist within the same territory while respecting that our non-human neighbours have their own norms and ways of navigating social life. So, how do we negotiate different aspects of living together when we hold different ideas of what is “good”?

That’s the work of doing politics. And other animals do, in fact, speak and act politically, as philosopher and artist Eva Meijer shows us.[55] They have their own pathways to express and to create meaning, be it individually or collectively, through different modalities of being in the world.[56] In their work on animal languages, Eva Meijer points out that the distinction between species does not stand in the way of understanding.[57] Rather, it is just one characteristic, among many others, that influences how meaning comes into being.[58] So, interactions between humans and other animals not only happen within a shared universe of meaning-making but can also lead to new meanings and understandings.[59] More so, they can lead to new material configurations.

Having different exchanges, across time and space, with urban animals, can be a way to engage politically with them.[60] If we pay close attention, we can notice that many of our non-human neighbours do in fact challenge the wrongs done to them. But they do so in ways that are not recognized as legitimate.[61] In a case study, Eva Meijer discusses how geese who persistently claim up a space for them, or return to an area where they are not wanted, contest human supremacy and how the land is occupied.[62] Similarly, with their presence, cats and dogs in my vicinity also defy particular anthropocentric norms and laws affecting their lives. They might also reject unfamiliar touches, run away, scratch humans, bark at cars, or fight against being caught. Surely, they don’t use words to make their case visible in the hegemonic political discourse, but they are not passive beings affected by human development. Urban animals challenge how the spaces we co-share are governed by disregarding particular arrangements. They vote with their feet when facing hostility or adverse conditions and protest human orders by physically occupying different locations.[63] And if their views are constantly trampled over they might resort to using their teeth! Either way, one thing is certain, they do push back against harms done to them. And they stand against anthropocentric claims to exclusive human ownership of territory.

These more-than-human ways of engaging politically emerge from specific contexts. While we can try to represent them in our political structures, speaking for others generally falls short in terms of doing justice to them. Self-representation is not only important for humans.[64] It matters for other animals too.[65] So, how can we do justice to their concerns, or respond to matters of collective concern? How can we do politics together?

– multispecies assemblies –

Drawing inspiration from anarchist and indigenous thought and practices, Eva Meijer sketches a model from which we can start.[66] They suggest we begin by forming multispecies assemblies.[67] Through them collective concerns can be explored and decided upon together with other beings.[68] Some humans might think this is not viable nor essential, or that it is impossible to communicate with other animals and understand them, let alone have political exchanges with them. But Eva Meijer points out how this skepticism is rooted in a form of speciesism.[69] It is one way in which particular societies and institutions silence embodied ways of engaging and exchanging information.[70] It is not an objective truth to regard other beings as voiceless, but a humanist construction with a particular, colonial, history.[71]

Meaning, for Meijer, emerges through different modes of being in the world.[72] Embodied interactions, along with the social and material configurations in which they take place, are what matters when we try to understand one another, human or non-human.[73] Multispecies assemblies can offer us a way of navigating different conceptions of what is “good”. They can include various beings, from non-human animals to other life forms, such as plants.[74] But also human children or the generations to come.[75] Most of these beings are typically left outside of decision-making processes today, because the adult neurotypical human is seen as the only legitimate being to decide or drive change. However, by living and relating differently with others and by addressing individual and collective concerns from the bottom up, we can help our non-human neighbours lead the way towards other arrangements.[76] It is about taking the matters into the hands, and paws, and branches, of local beings. The model that Eva Meijer proposes can provide a pathway to navigate present relations of domination carefully.[77] It not only fosters inclusivity and reconfigures decision-making processes to embrace other animals, but it can give more precedence to self-representation and horizontal and non-hierarchical forms of shaping our collective lives.[78]

Multispecies assemblies can play a vital role in doing justice to urban animals. For instance, they can influence local communities to move further away from anthropocentric values and nurture more welcoming and just arrangements in exchange.[79] It goes without saying that different urban spaces bring different problems for the non-human animals inhabiting them. So, paying close attention to some of the challenges they face in their territories can be one way to initiate an assembly. But urban animals may also express their disapproval of certain local practices, indicating the need for an assembly, intentionally or unintentionally.[80]

Think of an abandoned site or one intended for a future building. Uninhabited by humans for a long time, the quiet space might be frequently visited by neighborhood dogs and cats, although birds, rodents, and reptiles might also find it to be a good spot. Cats, for example, might see the unused pile of sand at the site as a place to relieve themselves, while dogs would eagerly come to search for daily surprises. Once the construction site is transformed into a paved area populated by unfamiliar and noisy humans, their daily routine will be affected. Thus, cats will be forced to use the neighboring sand from children’s playgrounds or humans’ vegetable gardens for the same purpose. Not only will this not be cleaned by dogs, but it would inevitably lead to conflicts with humans. More so, in the absence of a better alternative in the neighborhood, dogs might also start using the sidewalk more often to relieve themselves. In this sense, through the daily actions of our non-human neighbours a local issue might become visible. A new construction, and the removal of unpaved land, or of the space other animals enjoyed and relied on for different purposes in the neighborhood, could bring forward different conflicts and questions that will need to be addressed collectively. Once these are signaled out the assembly can be assessed and guided by a group of human and non-human facilitators.[81] These actors will unpack the issues and questions at stake. Their role will be to assess who is impacted, who can participate, and in what way interactions can unfold, among other things, trying to make sense of the process.[82] When the scope becomes clearer, those who make up the assembly will deliberate on the problems at stake.[83] Some dialogues will happen by the use of words, but there will also be embodied forms of communication and material interventions leading to a decision.[84] Perhaps, there’s a particular kind of sand that cats liked, an old building, or a quiet space that many other beings enjoyed. All of these aspects would need to be investigated and tested out through different social and material interventions. In many instances, and in the beginning, certain decisions will only steer the process of solving a particular issue at stake, rather than offer a final conclusion.[85] But after a while, the assembly could be dissolved if there’s no need for ongoing deliberations.[86]

Eva Meijer brings attention to multiple aspects in their work to better understand the contours of these multispecies assemblies. Some assemblies can be short-term, for instance, oriented on a particular issue perhaps similar to our previous example.[87] Others can be long-term, maintaining regular – or irregular – interactions to deliberate on shared concerns.[88] Assemblies can also be very different from one context to another.[89] So, reflecting over their duration and scope and re-evaluating them periodically is a crucial aspect, as their meaning and political purpose can change over time with the involvement of other beings.[90] It is important to ensure that others are equally considered in the process as well, instead of rushing to conclusions.[91] And so is to anchor the assembly in a precise location, as deciding with more-than-human others starts from situated engagements.[92] Multispecies assemblies should consider the various rhythms of life experienced by other beings involved.[93] And stay away from bureaucracy.[94] Eva Meijer speaks about getting to know others ethically, bending hierarchies through play, conversations that don’t revolve around words, and embracing the messiness of experimenting with alternative ways of living and organizing found in anarchist thought.[95] They notice how different ways of relating can lead to different knowledges.[96] While human assemblies ran into different challenges in previous movements, multispecies assemblies can spark a transformative process that goes beyond the current paradigm of speaking for other animals around us.[97]

Engaging in decision-making processes with other animals in ways that are more horizontal can certainly look like a stretch into other possible futures. However, it is not about a distant utopia that Eva Meijer speaks about but about gradually transforming the gardens, the streets, and the neighbourhoods in which we already live by engaging politically with other animals. Surely, it requires imagination and openness from us to other ways of doing politics. And it is about attuning to different timescales, languages, and more-than-human ways of being. But by changing cultural attitudes and practices within the city, in our surroundings, there is a way to resist its exclusiveness and violence. There is a way to move forward in the here and now.

Other animals already make the city their home. They are here with us on its alleys and narrow pathways. And they will always be, in some ways. We only need to make the public space a little bit safer, more welcoming and respectful towards more-than-human ways of living. And to include those around us in how we are going to do this! By experimenting with multispecies assemblies we get to learn how to be on other animals’ side. We get to speak with them, not for them. We get to take part in a dialogue that twists and turns, carving out a space that ripples with time.

to get to see us

oh you’ll need to look

to get to hear us

you’ll need to listen

to get to grasp us

you’ll need to be silent

be still

be still

In memory of Robin

Notes & bibliography

[1] See Claudia Towne Hirtenfelder, Cast Out Urbanites: The Historical Problematization of Cows in Kingston (Kingston: Queen’s University, 2023), 44, 51-52.

[2] For an in depth conceptualization of the process of problematization see Hirtenfelder, Cast Out Urbanites.

[3] See, for instance, Kelsi Nagy and Phillip David Johnson II, “Introduction,” in Trash animals: How we live with nature’s filthy, feral, invasive, and unwanted species, ed. Kelsi Nagy and Phillip David Johnson II (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013); Colin Jerolmack, “How pigeons became rats: The cultural-spatial logic of problem animals,” Social problems 55, no. 1 (February, 2008), doi: doi.org/10.1525/sp.2008.55.1.72; Roberto Marchesini, “Animals of the city,” Angelaki 21, no. 1 (April 2016), doi: 10.1080/0969725X.2016.1163825; Krithika Srinivasan, “Remaking more-than-human society: Thought experiments on street dogs as ‘nature’,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 44, no. 2(February 2019): 4, doi: 10.1111/tran.12291; Marie Carmen Shingne, “The more-than-human right to the city: A multispecies reevaluation,” Journal of Urban Affairs 44, no. 2 (April 2022): 6, doi: 10.1080/07352166.2020.1734014; Aron Nor, “Inamicii economiei socialiste, intrușii civilizației occidentale,” gând vagabond, June, 2022, https://gandvagabond.ro/inamicii-economiei-socialiste-intrusii-civilizatiei-occidentale/; Lauren E. Van Patter and Alice J. Hovorka, “‘Of place’ or ‘of people’: exploring the animal spaces and beastly places of feral cats in southern Ontario,” Social & Cultural Geography 19, no. 2 (January 2017), doi: 10.1080/14649365.2016.1275754.

[4] See Hirtenfelder, Cast Out Urbanites.

[5] See Hirtenfelder, 47-48.

[6] See Raymond Coppinger and Lorna Coppinger, What is a dog? (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016): 15-17.

[7] See Terry O’Connor, Animals as Neighbors: The Past and Present of Commensal Species (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2013): 7.

[8] O’Connor, 7, 127; Marchesini, 80, 86; Aron Nor, “Locul câinelui sinantrop, poziții confuze și politici comune,” Fractalia: Cunoașteri de frontieră (November 2022), 9-10.

[9] O’Connor, 7.

[10] O’Connor.

[11] For more details about the commensal relationship of dogs see Raymond Coppinger and Lorna Coppinger, Dogs: a new understanding of canine origin, behavior, and evolution (University of Chicago Press, 2002); See also Coppinger and Coppinger, What is a dog?.

[12] O’Connor, 8.

[13] See O’Connor, 8, 126.

[14] O’Connor, 126.

[15] O’Connor, 8.

[16] O’Connor, 101.

[17] See Raymond Coppinger and Lorna Coppinger, Dogs: a new understanding of canine origin, behavior, and evolution (University of Chicago Press, 2002); Raymond Coppinger and Lorna Coppinger, What is a dog? (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016).

[18] Coppinger and Coppinger, Dogs.

[19] See Mariam Motamedi Fraser, Dog politics: Species stories and the animal sciences (Manchester University Press, 2024); Ádám Miklósi, Dog behaviour, evolution, and cognition (Oxford University Press, 2007): 96; Mark Derr, How the dog became the dog: from wolves to our best friends (Abrams, 2011); Raymond Pierotti and Brandy R. Fogg, The first domestication: how wolves and humans coevolved (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017).

[20] Pierotti and Fogg, 196, 100.

[21] Pierotti and Fogg, The first domestication.

[22] Pierotti and Fogg, 5.

[23] Chris Pearson, Collared: How We Made the Modern Dog (London: Profile Books, 2024), 6, 60.

[24] Joelene Hughes and David W. Macdonald, “A review of the interactions between free-roaming domestic dogs and wildlife,” Biological Conservation 157 (January 2013): 342, doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2012.07.005.

[25] Pearson, 68; Chris Pearson, Dogopolis: How Dogs and Humans Made Modern New York, London, and Paris (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021), 37; Nor, “Inamicii economiei socialiste, intrușii civilizației occidentale”.

[26] Pearson, Collared, 68; Srinivasan, “Remaking more-than-human society”; Lavrentia Karamaniola, Bucharest Barks: Street Dogs, Urban Lifestyle Aspirations, and the Non-Civilized City (University of Michigan, 2017), 158-170; Nor, “Locul câinelui sinantrop, poziții confuze și politici comune,” 15.

[27] Pearson, 42-43, 69, 213.

[28] See Hughes and Macdonald; Kathryn Lord, Mark Feinstein, Bradley Smith and Raymond Coppinger, “Variation in reproductive traits of members of the genus Canis with special attention to the domestic dog (Canis familiaris),” Behavioural processes 92 (January 2013): 132, doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2012.10.009.

[29] See Coppinger and Coppinger; Coppinger and Coppinger, What is a dog?.

[30] See Coppinger and Coppinger, 43.

[31] See, for instance, Fabio S.T. Sweet , Anne Mimet, Md Noor Ullah Shumon, Leonie P. Schirra, Julia Schaffler, Sophia C. Haubitz, Peter Noack, Thomas E. Hauck and Wolfgang W. Weisser, “There is a place for every animal, but not in my back yard: a survey on attitudes towards urban animals and where people want them to live,” Journal of Urban Ecology 10, no. 1 (March 2024), doi: doi.org/10.1093/jue/; Vasilios Liordos, Evangelia Foutsa, Vasileios J. Kontsiotis, “Differences in encounters, likeability and desirability of wildlife species among residents of a Greek city,” Science of the Total Environment 739, no. 139892 (June, 2020), doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139892; Marchesini; Nagy and Johnson II.

[32] See, for instance, O’Connor, 118-120, 127.

[33] See, for instance, Marchesini; Nagy and Johnson II; Fabio S.T. Sweet et al.; Liordos, Foutsa and Kontsiotis.

[34] See, for instance, Fabio S.T. Sweet et al.; Liordos, Foutsa and Kontsiotis.

[35] See, for instance, Phil Hubbard and Andrew Brooks, “Animals and urban gentrification: Displacement and injustice in the trans-species city,” Progress in human geography 45, no. 6 (2021), doi: 10.1177/0309132520986221; Clare Palmer, “Colonization, urbanization, and animals,” Philosophy & Geography 6, no. 1 (2003), doi: 10.1080/1090377032000063315.

[36] On the topic of street dogs ”overpopulation” see Nor, “Inamicii economiei socialiste, intrușii civilizației occidentale”.

[37] Marchesini, 81.

[38] Marchesini.

[39] Pearson, 61.

[40] Nor, “Locul câinelui sinantrop, poziții confuze și politici comune”.

[41] See Pearson, Dogopolis; Pearson, Collared; Philip Howell, At Home and Astray: The Domestic Dog in Victorian Britain (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015).

[42] Pearson, 38, 48.

[43] Pearson, 48-51.

[44] See Pearson, Dogopolis; Pearson, Collared.

[45] Howell, 100.

[46] Yamini Narayanan, “Street dogs at the intersection of colonialism and informality: ‘Subaltern animism’ as a posthuman critique of Indian cities,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 35, no. 3 (2017): 479, doi: 10.1177/0263775816672860; Krithika Srinivasan, „The biopolitics of animal being and welfare: dog control and care in the UK and India,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 38, no. 1 (2013): 6, doi: 10.1111/j.1475-5661.2012.00501.x; Howell, 66, 100-101.

[47] See Srinivasan, “Remaking more-than-human society”; Aron Nor and Eva Meijer, Straying with street dogs: A dialogue on animal tainted politics (forthcoming).

[48] See, for instance, Karamaniola, 14, 155, 158, 210, 292.

[49] See Nor, 17; Nor and Meijer.

[50] See Nor; Nor and Meijer.

[51] See Nor; Nor and Meijer.

[52] A similar question, focusing more specifically on street dogs, is also explored in Nor and Meijer.

[53] See Sue Donaldson, “Animal Agora: Animal Citizens and the Democratic Challenge,” Social Theory and Practice 46, no. 4 (October 2020), http://www.jstor.org/stable/45302463; Eva Meijer, When Animals Speak: Toward an Interspecies Democracy (New York: New York University Press, 2019); Eva Meijer, Multispecies Assemblies (forthcoming).

[54] See Sue Donaldson’s and Will Kymlicka’s presentation. UCL Social & Historical Sciences, “Scales: Political, The Animal Scales seminar series is hosted by UCL Anthropocene,” recorded December 11, 2024, Youtube video, 1:28:21, https://youtu.be/smDHNjfzdR8?feature=shared; Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka, Animals and the Right to Politics (forthcoming).

[55] Meijer, When Animals Speak.

[56] Meijer.

[57] Meijer, 34, 65.

[58] Meijer, 34.

[59] Meijer, 74.

[60] Meijer, When Animals Speak.

[61] See Meijer, 224.

[62] Meijer, 175-176.

[63] See Meijer, 174-176.

[64] See CrimethInc., From Democracy to Freedom. The difference between government and self-determination (2017).

[65] Eva Meijer, Multispecies Assemblies (unpublished manuscript: VINE Press, forthcoming), 18.

[66] See Meijer, Multispecies Assemblies; See also Eva Meijer’s presentation, Котики и коровы: критические исследования животных, “Eva Meijer ‘Multispecies Assemblies’,” June 13, 2024, Youtube video, 1:05:43, https://youtu.be/CqQkczmjHew?feature=shared.

[67] Meijer.

[68] Meijer, 10.

[69] Meijer, 12.

[70] Meijer, 11-12.

[71] Meijer, 11.

[72] See Meijer, 12; Meijer, When Animals Speak.

[73] Meijer, Multispecies Assemblies, 12.

[74] Meijer, 25.

[75] Meijer.

[76] See Meijer.

[77] Meijer.

[78] Meijer; For a critical interrogation of direct/participatory democratic models and the need also for self-determination, horizontality, and decentralization see CrimethInc.

[79] Meijer.

[80] Meijer, 25, 29.

[81] Meijer, 25, 34.

[82] Meijer, 34.

[83] Meijer.

[84] Meijer.

[85] Meijer, 35.

[86] Meijer.

[87] Meijer, 25, 27.

[88] Meijer.

[89] Meijer, 26.

[90] Meijer, 27, 33.

[91] Meijer, 31.

[92] Meijer, 33.

[93] Meijer, 32-34.

[94] Meijer, 26.

[95] Meijer, 27.

[96] Meijer, 29-30.

[97] For understanding some of the issues human assemblies ran into see CrimethInc., From Democracy to Freedom.